Most Oregonians will never see one of Oregon’s wolves. Very few of the people involved in the following story have.

Most Oregonians will never see one of Oregon’s wolves. Very few of the people involved in the following story have.

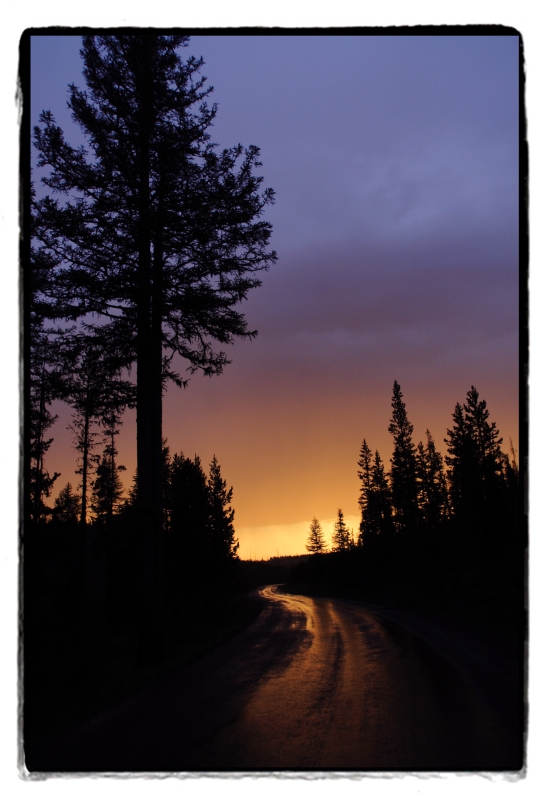

Although seven of these images were already printed in a story entitled, “Wolves of the Wallowas” for the Fall 2010 issue of “1859- Oregon’s Magazine”, this photo project will continue for me personally until I am one of the people who has seen them, and photographed them, and likely beyond that. For now, at the end of this blog I have included two Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife public use images of Imnaha and Wenaha wolves (the latter was shot and killed by a poacher in the Fall of 2010.)

This issue is not just about wolves though, it’s about people. Some of those people and their stories you will find in the following pages. I hope that it sheds some light on the varying perspectives of those involved with, and affected by the return of the wolf to Oregon.